This month, I expect my time to be taken up with cereals – planting rye, perhaps preparing the ground for the winter wheat, and probably harvesting the buckwheat (which is not strictly speaking a cereal, but plays a similar role in the diet). I know that we are in a small minority even amongst keen gardeners in trying to grow our own cereals, but there are many good reasons why more people should think about taking up the challenge.

Reasons to Grow Cereals

The way that food is presented in shops and supermarkets makes it difficult to identify the original ingredients of any particular product; and a lot of people assume that cereals do not play a particularly large role in the modern diet. But, after a little reflection one realises that cereals are not only used in breads, biscuits, cakes, and pastries, but that rice is also a cereal, pasta is made from wheat, maize is used in one form or another in all sorts of products, most of the meat in the shops comes from cereal-fed animals, most dairy cows are given cereal-based supplements, you have to feed chickens cereals if you want them to lay eggs, beer is usually made from barley, and breakfast cereals, muesli, and granola are all cereal based. Cereals are still our staple food, and without them life would be quite different. The problem is that we no longer know where our cereals come from, how they are grown, and what the true environmental cost of their production might be.

Global cereal production is one of the modern industries that is built on the legacy of the colonial and imperial politics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It exploits lands that were once home to indigenous, self-sufficient communities, using new technologies that include satellite-guided machines, chemical fertilisers, gene manipulation, and chemical sprays, plus a sophisticated infrastructure of ports and shipping lines that make it possible to deliver vast quantities of grain to anywhere in the world, undercutting the viable market price for any small-scale, sustainable produce in the area.

All of this provides ample reason to grow cereals for oneself, not only because one might have concerns about the health and environmental issues associated with food produced in this way, but also because it is a practical way to register one’s opposition to the overall system.

Some Practical Tips

The first point to appreciate is that there is very little relevant information about garden-scale cereal growing. Knowledge possessed by the farming industry of how to produce a crop using modern varieties, a tractor, a combine harvester, and nitrogen fertiliser, does not transfer to a hand-worked plot, and even if one lives in a farming area, it is difficult to find anyone who can remember anything about how cereals were grown prior to the modern era. So your main guide has to be your common sense, plus trial and error.

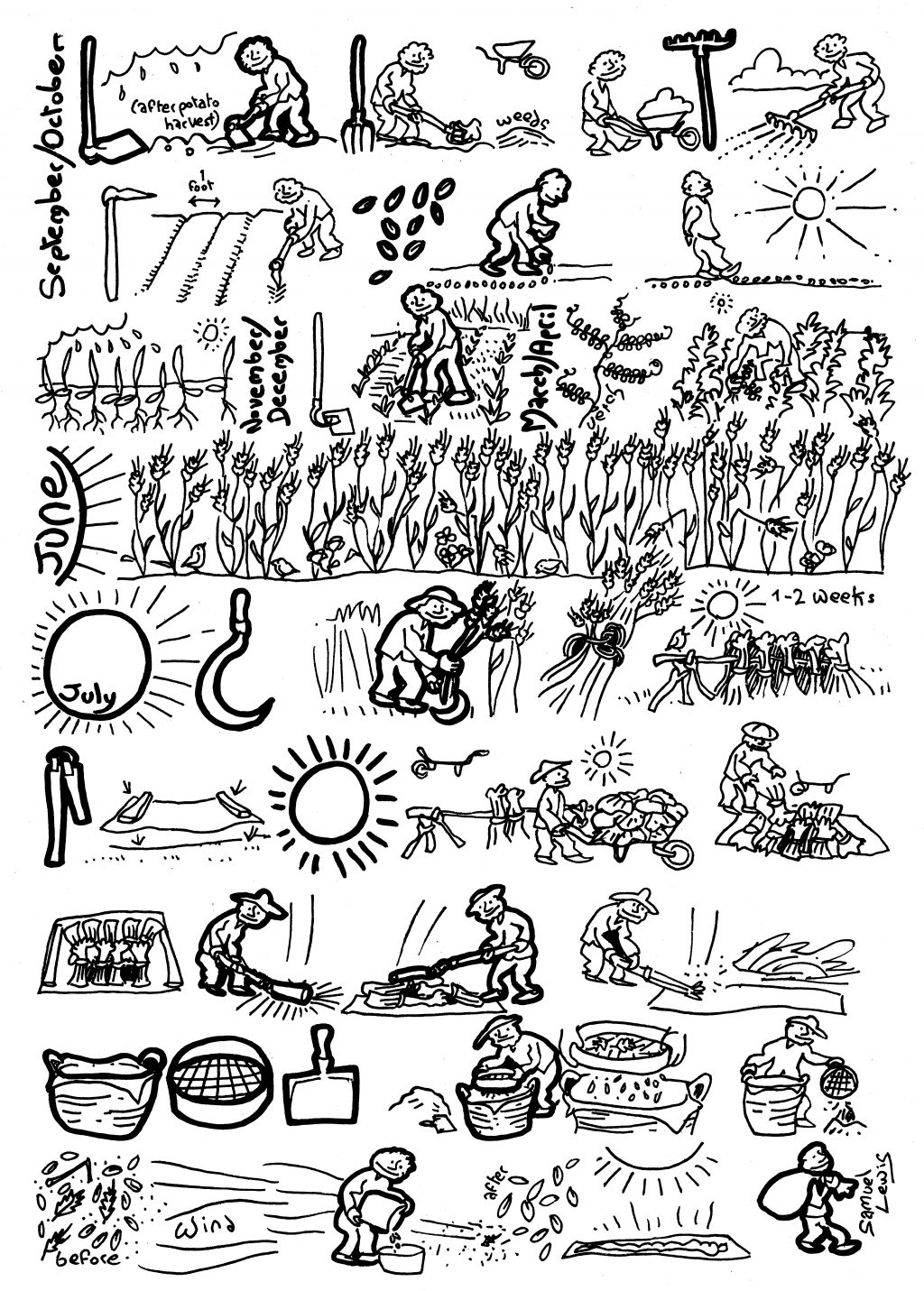

The second point is to start small, and to start soon. There is no reason why a small plot of wheat, rye, or barley should not be incorporated into a vegetable garden. Learning the basic techniques of sowing, weeding, cutting, and extracting the grain is best done on a few plants before you invest more time and energy into a larger plot.

The third point is that it may take a few years before you work out which cereals and which varieties to grow. The process cannot be rushed. In the modern world, the environment is made to conform to what we imagine to be our needs: the same machines, the same varieties, and the same techniques are used all over the world, over vast areas of land. When working by hand you have to be more humble and adapt yourself to the demands of nature. It takes time to work out which cereals can be grown in your area, how to harvest and process them, when to sow them, and how to prepare your ground, and much of what you learn will be specific to your own locality.

In our case, we did not think of trying to grow rye until we had experienced several years of poor wheat crops, and a few experiments with oats and barley. It was only after we started to grow rye that elderly neighbours told us that that was the crop that they saw growing in the fields when they were young. We grow a patch of buckwheat every year, because everyone says that it is a local crop, but we still have not found the exact formula to give a reliable harvest.

The good news is that even when you do not really know what you are doing, and are a long way from cereal self-sufficiency, you still usually get some form of harvest, and have a sense that you are starting to make progress in rediscovering an ancient and forgotten skill.

Gareth Lewis

Feedback

Always enjoy your writings/artwork.

I seem to have good success sowing buckwheat in July after favas (broad beans) or garlic here in Pennsylvania. I cut it in late September/early October when most of the seeds have ripened but usually has some green leaves still. I guess I should mention I grow Japanese buckwheat. Never tried the tartary. Don’t know if any of this may help but figured I would send along.

Patrick Ciarrocchi, Ridgeview Farm, Peru Mills, Pennsylvania, USA